What Are Articles?

Articles—we use them every day, but do we know the meaning of them? You definitely will after this post because here, we’ll be talking about the German articles. Not the ones in the newspaper, but those used in grammar.

So, what are articles? The definition is pretty clear. They belong to a group of words which we call determiners and we link them to nouns. With an article we can determine the noun we are using. Important to know: the article always goes in front of the noun.

In English, the articles are for example:

- the (definite)

- a / an (indefinite)

In German, there are some more articles, and after reading through this post you’ll be familiar with most of them, and know exactly how to use them.

So, take one last bite of your “Brezel” because you’re about to get a mouthful of articles!

The pretzel? - A pretzel? - My pretzel!

- An article determines the noun we are using.

- The article always goes in front of the noun.

The German Definite And Indefinite Articles

Just like in English, there are definite and indefinite articles in German. “What is a definite or an indefinite article?”, you might ask.

I’ll tell you. We use an indefinite article when we are introducing a noun for the first time, and the noun is not known to us yet.

- Das ist ein Apfel. (This is an apple.)

We use the definite article when we have already introduced our noun to the conversation and we are talking specifically about this one noun that we already know.

- Der Apfel ist rot. (The apple is red.)

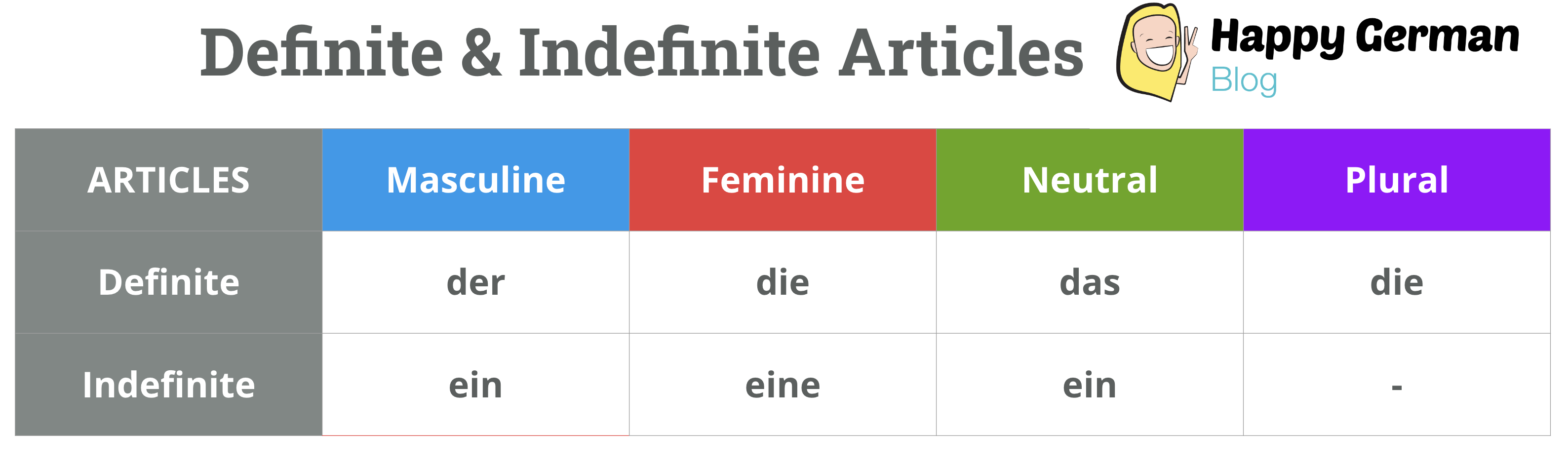

Check out the table below with the German definite and indefinite articles.

Here are some more examples with the German definite and indefinite articles.

- Das ist ein Baum. Der Baum ist groß. (This is a tree. The tree is tall.)

- Das ist eine Blume. Die Blume ist schön. (This is a flower. The flower is beautiful.)

- Das ist ein Auto. Das Auto ist neu. (This is a car. The car is new.)

- Das sind - Kinder. Die Kinder sind laut. (These are - kids. The kids are loud.)

→ As you can see, there is no plural form of the indefinite article, just like in English.

One thing you should know about German articles: they change their form according to the gender of the noun (as you could see in the examples above). Additionally, they change according to the grammar cases that need to be applied. So far, we are using the Nominative case. If you wanna dig deeper, we have posts for you on the Accusative, Dative and Genitive cases.

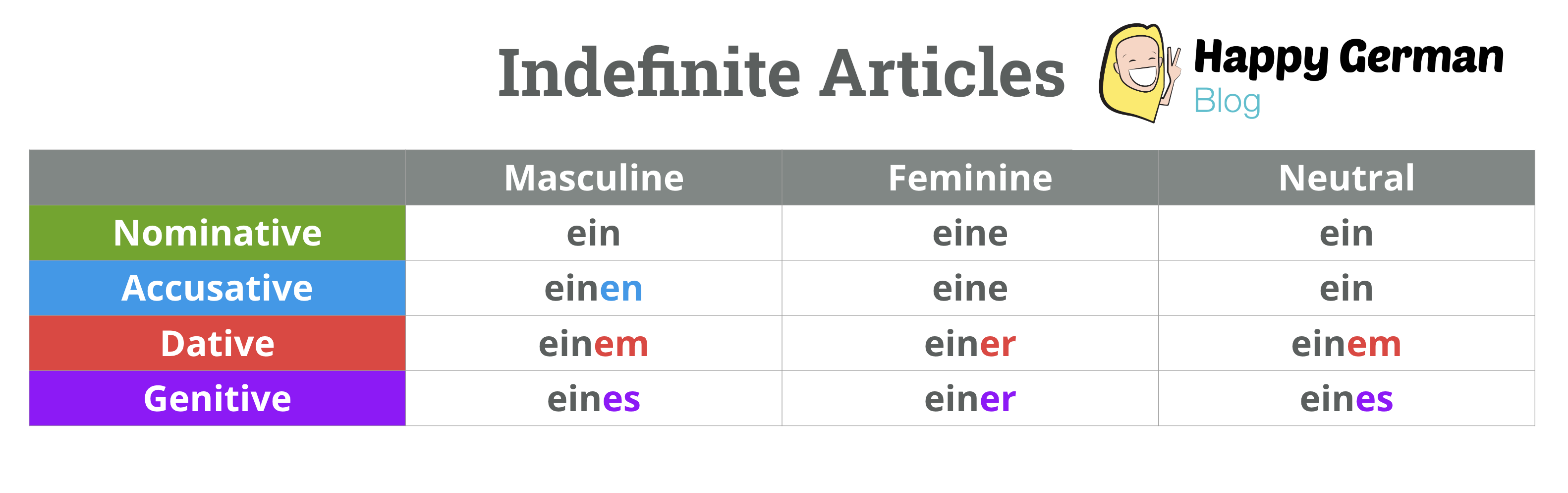

Below, you'll find the grids for all definite and indefinite articles in singular and plural, and according to all four German cases:

Indefinite articles...

- ...introduce a noun/ idea/ person for the first time.

Definite articles...

- ...are used with nouns that have already been mentioned.

German articles change:

- according to gender: masculine, feminine, neutral

- according to plurality: singular, plural

- according to cases: Nominative, Accusative, Dative, Genitive

How To Know Which German Articles To Use

Now that we know what articles are, we can jump to the next question that always arises : How do I know which article I have to use? In English, things are pretty easy because every specific or plural noun has the article “the”. But in German, things are a bit different. German nouns can be masculine, feminine or neutral.

And here is where the confusion starts. In English the noun “moon” has the article “the” when we’re talking specifically about "the moon" in our solar system. In Italian and Spanish, and many other languages, it’s a feminine noun ("la luna"), and in German it’s masculine ("der Mond"). I’ll give you a few hints on how to know which articles to use.

The German Masculine Article “der”

Use the German masculine article "der" for:

- Male people, animals, professions: der Mann, der Student, der Vater, der Tiger, der Bäcker (the man, student, father, tiger, baker)

- Days of the week, months, seasons, directions: der Montag, der Januar, der Frühling, der Süden (Monday, January, spring, south)

- Nouns with specific endings: der Häuptling, der Elefant, der Zirkus, der Teppich (the chief, elephant, circus, carpet)

- Many nouns deriving from verbs without the ending “-en”: schlafen → der Schlaf (to sleep → the sleep)

The German Feminine Article "die"

Use the German feminine article “die” for:

- Female people, animals, professions: die Frau, die Schwester, die Löwin, die Journalistin (the woman, sister, lioness, journalist)

- Most German rivers: die Elbe, die Mosel, die Oder (the river Elbe, Moselle, Oder)

- Nouns with specific endings: die Zeitung, die Logik, die Meisterschaft, die Universität, die Therapie, die Resistenz, die Struktur, die Wahrheit, die Freundlichkeit, die Bäckerei, die Aktion (the newspaper, logic, championship, university, therapy, resistance, structure, truth, friendliness, bakery, action)

The German Neutral Article "das"

Use the German neutral article “das” for:

- Letters of the alphabet: das A, das B, das C, ... (the A, B, C, ...)

- Nouns with specific endings: das Experiment, das Universum, das Eigentum (the experiment, universe, property)

- Nouns with diminutive endings: das Mädchen, das Häuslein, das Zuckerl (the girl, little house, Austrian German for candy)

- Nouns derived from a verb in its infinitive form: das Essen, das Trinken, das Lesen (the eating, drinking, reading)

- Nouns derived from English with the ending “-ing”: das Training, das Timing (the training, timing)

- Collectives beginning with “Ge-”: das Gebäck, das Gebirge (the pastries, mountain range)

Check out our detailed post of how to make sense of German noun genders with many examples, and all the great hints about how to use the articles correctly!

A little disclaimer: Although there are many rules which help you remember the articles better, there are also many tricky exceptions. Therefore, I would recommend you always learn new nouns together with their respective articles. Also: Do not ask yourself why a German noun even has a specific gender. In a lot of languages it does not make any sense.

Take a little break, and watch Anja's video on that topic!

The German Zero Article

As your brilliant mind might suspect, the zero article means that there are sentence structures where we don't use any article in front of a noun. This happens in some specific situations that you’ll learn now.

Indefinite Plural Nouns

One case where you don’t need to use an article is when you have indefinite nouns in the plural. As we learned in the section above, we have indefinite articles and there is no plural form of them. This means that we won’t use any articles in front of the noun in plural.

Let's see:

A sentence with a noun in singular introduced by an indefinite article will look like this:

- Da steht ein Baum. (There is a tree.)

- Sie hat eine Katze. (She has a cat.)

- Wir haben ein Buch. (We have a book.)

→ We mention a tree, a cat, a book for the first time, which means we use indefinite articles. In German they look different depending on the gender of the noun, which can be masculine, feminine, or neutral.

The same sentences with the nouns in plural look like this:

- Da stehen Bäume. (There are trees.)

- Sie hat Katzen. (She’s got cats.)

- Wir haben Bücher. (We have books.)

→ The trees, cats, and books are also mentioned for the first time. Like in English, there is no article when the nouns are not defined. In German, there is no gender in plural nouns. (Exceptions are male/ female people, animals, and professions.)

Proper Names Without Adjectives

When using proper names without any adjectives before them, you also omit the article.

- Ich tanze mit Gogo. (I’m dancing with Gogo.)

- Er arbeitet bei Lidl. (He works at Lidl.)

Things will look a little bit different when you have an adjective before the name because you will have to add an article. It’s not the most common thing to do, but it’s used to make sure that the person you’re talking to really understands who or what you’re talking about.

- Ich tanze mit dem netten Gogo. (I’m dancing with the nice Gogo.)

- Er arbeitet beim neuen Lidl. (He works at the new Lidl.)

Note: Just like in English, there are certain German proper names with articles.

Here are some examples:

- der Deutsche Bundestag (the German Bundestag, also: the German Parliament)

- die Semperoper (the Semper Opera House)

- das Brandenburger Tor (the Brandenburg Gate)

- die Olympischen Spiele (the Olympic Games)

Measurements Phrases

In the following cases we have the infamous zero article again, and don’t need to add definite or indefinite articles.

- Die Gäste trinken 10 Liter Bier. (The guests drink 10 liters of beer.)

- Sie kauft fünf Eier. (She buys five eggs.)

- Er trinkt eine Tasse Tee. (He drinks a cup of tea.)

- Wir essen ein Kilogramm Nudeln. (We eat a kilogram of pasta.)

→ In the last two examples, the indefinite articles refer to the measurement, one cup and one kilogram respectivly. The articles do not refer to the tea/ pasta.

Abstract Nouns

For German abstract nouns there is no need to use articles, just like in English.

- Sie beweist viel Mut. (She’s showing a lot of courage.)

- Stefanie hat Angst vor Spinnen. (Stefanie is afraid of spiders.)

- Wir brauchen Hilfe. (We need help.)

Nationalities and Languages

When talking about nationalities and languages you can skip the article without any problem!

- Er ist Italiener. (He’s Italian.)

- Sie lernen Deutsch. (They’re learning German.)

- Katie und Jan sprechen Französisch. (Katie and Jan speak French.)

- Laura ist Spanierin. (Laura is Spanish.)

Countries And Cities Without Adjectives

- Wir kommen aus Deutschland. (We’re from Germany.)

- Kommst du aus Spanien? (Do you come from Spain?)

- Sie kommt aus Berlin. (She’s from Berlin.)

- Barcelona ist eine schöne Stadt. (Barcelona is a beautiful city.)

Most German names for countries and cities are used without articles. But be careful! There are some sneaky exceptions of countries that do require an article!

- die Schweiz (Switzerland) - Sie kommt aus der Schweiz. (She’s from Switzerland.)

- die Türkei (Turkey) - Er lebt in der Türkei. (He lives in Turkey.)

- der Libanon (Lebanon) - Wir reisen in den Libanon. (We travel to Lebanon.)

- die USA (the US) - Wir arbeiten in den USA. (We work in the US.)

And just like with the proper names in the previous paragraph, we can add an article to the noun when there is an adjective, and we specifically talk about this one city, country or region.

- Sie kommt aus dem schönen Berlin. (She comes from beautiful Berlin.)

- Ich lebe im sonnigen Spanien. (I live in sunny Spain.)

Here is a 100 points question: which city is this?

Das ist das Brandenburger Tor im schönen Berlin.

That's the Brandenburg Gate in beautiful Berlin.

The Zero Article For Professions

When we talk about professions, and use the verbs “sein” (to be) or “werden” (to become) or the conjunction “als” (as).

- sein (to be) - Gogo ist Lehrer. (Gogo is a teacher.)

- werden (to become) - Katie will Tierärztin werden. (Katie wants to become a veterinarian.)

- als (as) - Sie arbeiten als Kellner und Kellnerinnen. (They work as waiters and waitresses.)

The German Possessive Articles

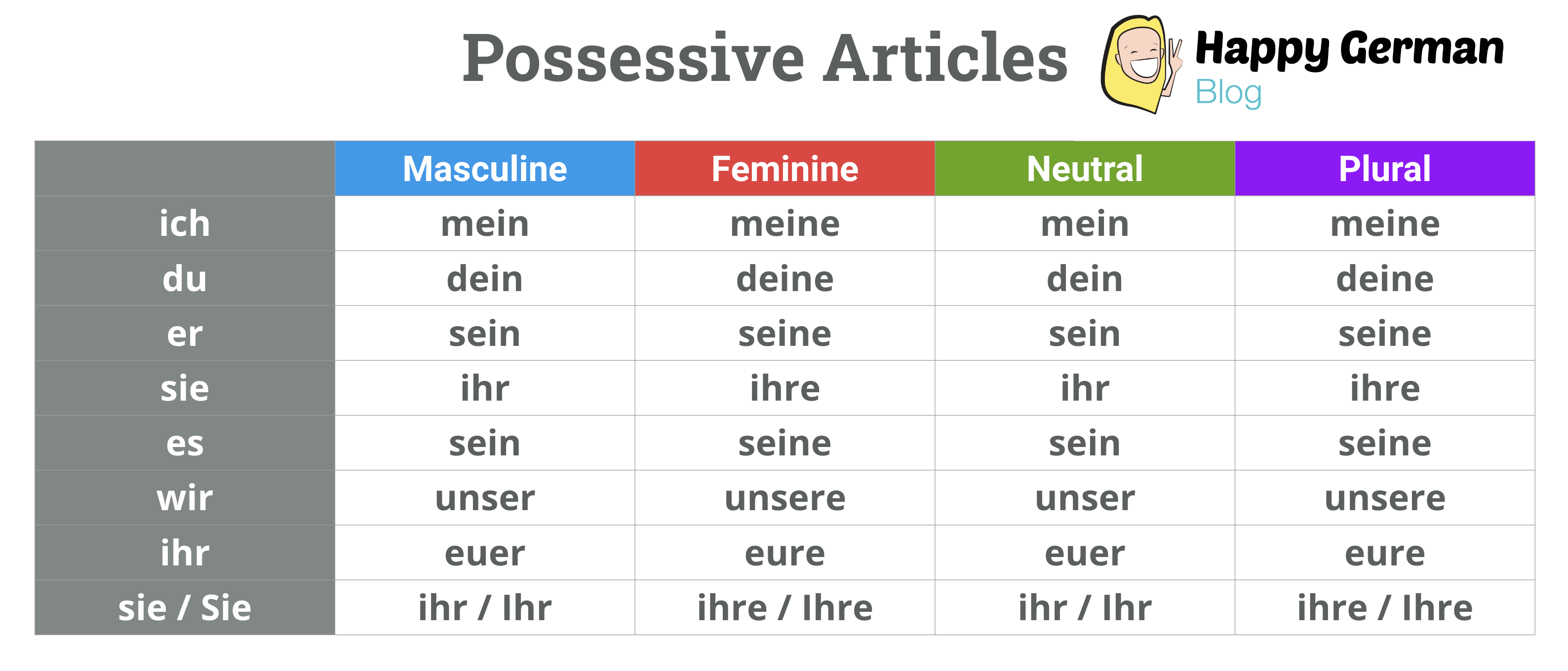

Possessive articles are determiners, just like definite and indefinite articles. They belong to the nouns and cannot be used alone, only in connection with nouns. The possessive articles indicate possession or belonging.

The possessive articles change depending on...

- the person: mein, dein, sein, ... (my, your, his, ...)

- the plurality: singular or plural

- the gender they refer to

Here’s a table with all the German possessive articles at a glance.

Let’s have a look at some examples:

- Ist das dein Kaffee? Ja, das ist mein Kaffee. (Is this your coffee? Yes, this is my coffee.)

- Das sind Katie und ihr Hund. (These are Katie and her dog.)

- Wie ist Ihr Name? (What is your name?)—Note that this is the formal way of asking someone's name. The informal way looks like this: Wie ist dein Name?

- Das ist Christian und das ist sein Bruder. (This is Christian and this is his brother.)

- Das ist mein Bruder und das sind unsere Eltern. (This is my brother and these are our parents.)

Dig deeper into the topic of the possessive articles and watch Anja’s video. You will find plenty of exercises to practice with Anja. Have fun!

The German Negative Articles

Negative articles are used to explain when “something is not” there. While in English there is one principal way to express that—with the simple negation "not", in German there are two different words and ways to say that something is not there.

The two magic words are “nicht” and “kein”. Now, I can already see that look on your face, asking me how to know when to use “nicht” and when to use “kein”.

So, let's break it down:

We use “nicht” to negate verbs, adjectives, and adverbs.

Here are some examples for you. You'll find a positive and a negative version for each:

- the verb "verstehen" (to understand) - Ich verstehe. Ich verstehe nicht. (I understand. I don’t understand.)

- the adjective "lustig" (funny) - Du bist lustig. Du bist nicht lustig. (You’re funny. You’re not funny.)

- the adverb "immer" (always) - Wir sind immer pünktlich. Wir sind nicht immer pünktlich. (We’re always punctual. We’re not always punctual.)

If you are looking for an explanation of where to put the "nicht" in a sentence, we are busy preparing a post for you.

For now, let's move forward with when to use "kein":

We use “kein” to negate nouns.

Check out the grid with all the forms of the German negative articles:

Let's have some examples—each with a positive and negative version—to make it clearer:

In Singular

- der Apfel (the apple) - Das ist ein Apfel. Das ist kein Apfel. (This is an apple. This isn't an apple.)

- die Pfeife (the pipe) - Das ist eine Pfeife. Das ist keine Pfeife. (This is a pipe. This isn't a pipe.)

- das Beispiel (the example) - Das ist ein Beispiel. Das ist kein Beispiel. (This is an example. This isn't an example.)

→ After the verb "sein" (to be) we use the articles + nouns in the Nominative case. The first sentence in each of the above examples is the positive version with an indefinite article + noun. The second sentence in each example is the negated form. The negation is shown in a negative article in front of the noun.

In Plural

- Äpfel (apples) - Das sind Äpfel. Das sind keine Äpfel. (These are apples. These aren’t apples.)

→ Again, after the verb "sein" (to be) we use the articles + nouns in the Nominative case. The first sentence is the positive version with no article (zero article for indefinite plural nouns) because the plural noun is not defined. In the second sentence, we negate the noun. The corresponding negative article is "keine".

Let's check some more examples in singular and plural, and with a mix of the cases:

- Ich rauche keine Pfeifen. (I don't smoke pipes.)

→ After the verb "rauchen" (to smoke), we need the Accusative case. Unlike in English, where we negate the verb "don't smoke", in German we negate the noun if there is one. The Germans would say "Ich rauche nicht.", to state that they do not smoke. In this case they negate the verb, just like in English. But when they add a noun (Pfeifen - pipes; Zigaretten - cigarettes) they rather negate the noun.

- Ich weiß von keinem Gewitter. (I don't know of any thunderstorm.)

→ The preposition "von" is always followed by the Dative case. Again, in English we negate the verb ("don't know"), while in German the noun ("Gewitter" - thunderstorm) is negated.

- Wir sind uns keiner Schuld bewusst. (We are unaware of any guilt.)

→ Now here's an example of a different form of negation in English. The English version of the sentence negates the adjective with the prefix "un-", rather than the usual way (using "not").

As you can see, in German, again, the noun ("Schuld" - guilt) is negated. Additionally, the German adjective "bewusst" (aware) combines with the Genitive case. If you'd like to know more about adjectives combining with certain cases, we have you covered.

Time to wrap it all up in a nice little quiz, don't you think? I challenge you

Quiz: The German Articles

The world of articles is fun! It can be a bit challenging at times, but if you follow the rules, and practice a lot, I promise you won’t have any problems with them.