When Do We Use The Dative Case in German?

Hello there, dear German student. In this post we're going on a grammar adventure to take a closer look at the Dative case!

We use the German Dative case after verbs that indicate giving and receiving. That often corresponds to what's called the "indirect object" in an English sentence.

We also use it after certain prepositions. Some of them require the Dative case only and others are so-called two-way prepositions (Wechselpräpositionen) that can be used with the Accusative or the Dative case. We’ll get back to that later.

Ok, let's answer the question you're no doubt asking yourself. What is an "indirect object" (in an English sentence)? In short, it's an object in a phrase introduced by "to" or "for", or set by word order, that makes it the "receiver" of an action.

Why don't we rather have a look at some practical examples?

- Der Mann ist nett. (The man is nice.)

→ “Der Mann” is in the Nominative case. It’s the subject and “the star” of the sentence.

Now we move on to the Dative, where the man is no longer the star of the sentence.

- Ich helfe dem Mann. - I help the man.

→ “Ich” became the subject of the sentence, the one who is performing the action, while “dem Mann” is now the object of the sentence (in the Dative case), in this case the person who receives the action.

In German, if we want to be sure whether we are using the Dative case or not, we use the question “wem?” (whom) or “was?” (what) and a verb, e.g.:

- Wem oder was helfe ich? (Whom or what am I helping?)

If you have impeccable attention to detail, then you might have noticed that we used a new article. Isn’t it “der Mann”? Yes, you are right, the Nominative article for masculine nouns is “der”. But why is it now “dem”? This is because we have entered the world of the Dative case.

What Is The Dative Case?

The Dative case typically has to do with giving or receiving. But, of course there are also other situations, verbs and prepositions that call for the Dative. In English, you might get to this kind of object/ case by asking: To (or for) whom am I giving (doing) this?

Fun fact!

Did you know that the word “Dative” (case) derives from

the latin word (casus) dativus and refers to dare (give) and datum (given)?

As we mentioned earlier, the Dative case corresponds to the idea of an "indirect object" in an English sentence. An indirect object is a person, or a thing or a pronoun that is affected by the action of a so-called "transitive" verb, but is not the primary object.

- Ich gebe ihm das Buch. - (I’m giving the book to him.)

- Gogo kauft ihr ein neues Kleid. - (Gogo buys a new dress for her.)

It can be hard to differentiate between the indirect (Dative) and the direct (Accusative) object. That’s why it helps to apply the following rule instead:

The Dative is used after certain verbs and prepositions.

How Do We Form The German Dative Case?

Take a look at the table and spot the difference in the articles between the Nominative and the Dative case.

Too many changes at once? Don’t worry, here are some examples of all three cases mentioned earlier to help you understand the Dative case better.

- Nominative case - Das ist der Vater. (That is the father.)

- Accusative case - Ich sehe den Vater. (I see the father. )

- Dative case - Ich helfe dem Vater. (I help the father.)

- Nominative case - Sie bleibt die Mutter. (She'll stay the mother.)

- Accusative case - Ich brauche die Mutter. (I need the mother. )

- Dative case - Ich glaube der Mutter. (I believe the mother.)

- Nominative case - So wird das Kind. (That's how the child will be.)

- Accusative case - Ich kenne das Kind. (I know the child.)

- Dative case - Ich danke dem Kind. (I thank the child.)

So far so good. You’ve probably noticed that in our examples we used sets of different verbs for the different cases.

- sein (to be), bleiben (to stay), werden (to become) + Nominative case

- sehen (to see), brauchen (to need), kennen (to know) + Accusative case

- helfen (to help), glauben (to believe), danken (to thank) + Dative case

I highly recommend you memorize them, because it will make it much easier for you to use the cases correctly. Check the list of verbs that are followed by the Dative in the next paragraph.

Now, in plural the endings of the nouns are also affected by the Dative, but only if they do not already end in -s or -n.

Here is what I mean:

- Ich danke den Männern. (I'm thanking the men.)

→ Dative case after the verb "danken" with an additional -n added to the plural form of "Männer" (men). All nouns that don't end in -s or -n in plural take that special ending.

Examples of plurals ending in -n or -s:

- Ich helfe den Eltern. (I'm helping the parents.)

→ "die Eltern" already has the ending -n in the plural, so we don't add the Dative plural ending -n.

- Ich helfe den Zebras. (I'm helping the zebras.)

→ "die Zebras" ends in -s and doesn't take the Dative plural ending -n.

Ich helfe meinen Nachbarn.

(I am helping my neighbors.)

Let’s take a break and watch a video of Anja explaining the Dative articles. It’s fun!

The German Dative Case After Certain Verbs

There are some verbs that you can rely on like your best friend when it comes to the German Dative case. Although the list of verbs that take the Accusative is much longer, there are some verbs that are always followed by the Dative.

In a dictionary you can see whether

a verb takes the Dative case by the abbreviation next to it.

When you see “jdm” this means jemandem (to somebody/someone),

and the ending -m tells you that this verb takes the Dative case.

Bonus Fact

When you see the abbreviation “jdn”

it means “jemanden” (somebody/ someone),

which indicates the Accusative case.

Here is a list of some of the most common verbs that are followed by the Dative.

- antworten (to answer) - Wir antworten dem Lehrer. (We answer the teacher.)

- danken (to thank) - Wir danken den Personen. (We thank the people.)

- gehören (to belong to) - Der Hund gehört der Frau. (The dog belongs to the woman.)

- glauben (to believe) - Ich glaube dem Mann. (I believe the man.)

- helfen (to help) - Ich helfe einem Kind. (I help a child.)

- schmecken (to taste) - Das Eis schmeckt dem Mädchen. (The ice cream tastes good to the girl.)

As mentioned earlier, these are some of the common verbs that require the Dative case, but not all of them.

Dative In Combination With The Accusative

Oh good, you’re still with me. Alright, take out your binoculars and watch what happens when the Dative meets the Accusative case.

Maybe, in one of Anja’s videos you learned that most of the German verbs need the Accusative case. So far so good. However, there are SOME verbs that take both the Dative and the Accusative case.

- geben (to give): Ich gebe dem Mann den Fisch. (I give the fish to the man.)

- zeigen (to show): Ich zeige meinem Mann den Park. (I show the park to my husband.)

- empfehlen (to recommend): Ich kann dir einen schönen Ort empfehlen. (I can recommend a nice place to you.)

Were you able to define which was the Dative and which was the Accusative? - You are correct!

→ The Dative is marked red (= "indirect" object in the English sentences) and

→ the Accusative is marked blue (="direct" object in the English sentences).

You can recognize the case by the changes in the articles, adjective and noun endings. Let's break it down for the first of the above examples:

- Ich gebe dem Mann den Fisch. (I give the fish to the man.)

→ "dem Mann" is with the Dative article "dem" rather than Nominative ("der Mann"). In a sentence, the Dative object is the receiver of an action, person or thing.

→ "den Fisch", is with the Accusative article "den" rather than "der Fisch" (Nominative). In a sentence, the Accusative object is the one that things are happening to.

→ In our example the fish ("den Fisch") is what I ("ich") am giving to the man ("dem Mann").

After verbs with two objects,

very often the person (living object) is in the Dative case,

while the “things” (non-living objects) are in the Accusative case.

Accusative and Dative? - Don't worry!

See that?

- Mach dir keine Sorgen. (Literally: Do make no worries to yourself. Or rather: Don’t worry.)

You analysed that almost in your sleep, didn’t you?

→ The verb "machen" (to make) takes two objects here:

→ "dir" is the receiver. It's the Dative pronoun for "du" (you).

→ "keine Sorgen" is the one things are happening to. It's the plural of "die Sorge" (worry) with a negative article in plural ("keine" - no) and the case is Accusative.

If you are looking for an overview of all cases, we got you covered. Go to the paragraph "What Are The German Cases?" and read up on the Nominative, Accusative, and Dative.

Now, if you want to practice the combination of Dative and Accusative a little bit more, watch Anja’s video below!

Dative Case After Certain Prepositions

There is a popular mnemonic in German that will help you memorize the prepositions that take the Dative case:

mit, nach, von, seit, aus, zu, bei - verlangen immer Fall Nummer drei!

(mit, nach, von, seit, aus, zu, bei - always require case number three!)

The Dative case is case number 3 in German.

The wonderful thing is that these prepositions will always be followed by the Dative case, no exception here!

Ok, I haven’t been entirely honest with you. There are three more prepositions: ab, außer and gegenüber, which sadly, do not fit into the cute little poem. But I will add them to the list below so that you can memorize them as well.

Here are some examples with Dative case prepositions that will help you.

- mit (with)- Wir fahren mit dem Auto. (We are going by car. Literally: We are driving with the car.)

- nach (after)- Nach der Arbeit gehen wir spazieren. (After work we go for a walk.)

- von (from, of, by)- Das Geschenk ist von meiner Mutter. (The present is from my mother.)

- seit (since)- Seit dem Abendessen habe ich Bauchschmerzen. (Since dinner I have had a stomach ache.)

- aus (out of, from)- Er kommt aus seinem Büro. (He's coming out of his office.)

- zu (to)- Die Frau geht zum Arzt. (zu + dem = zum) (The woman goes to the doctor.)

- bei (at, near)- Sie wohnt bei meinem Nachbarn. (She lives at my neighbor’s.)

- ab (off, from)- Ab dem ersten September. (From the first of September.)

- außer (except)- Alle sprechen Deutsch außer mir. (Everybody speaks German except me.)

- gegenüber (opposite, across)- Wir wohnen gegenüber vom Park. (We live across the park.)

Here is another wonderful video of Anja using the Dative prepositions. Believe me, you will love it and you will have the song stuck in your head for the next couple of days!

Alrighty. Take another deep breath, get ready and let’s soar into the next use of the Dative case.

The Dative Case With Two-Way Prepositions (Wechselpräpositionen)

Please give a warm welcome to our bisexual set of prepositions, the two-way prepositions (Wechselpräpositionen). They have that peculiar name because they behave like this: Sometimes they like the Dative and some other times they like the Accusative case.

Below, there is an overview of the most common prepositions, grouped according to the grammatical cases they're followed by, and as you can see, they merge in the middle as the so-called “Wechselpräpositionen” (two-way prepositions).

How do we know when to use the Accusative or Dative case after those two-way prepositions?

To start with, all two-way prepositions are local prepositions (as opposed to temporal prepositions, for instance).

With local prepositions we say

- where someone or something is:

→ The Germans ask "wo?", and...

→ ... you usually find a static verb in the sentence, followed by one of the two-way prepositions.

→ The noun that follows the preposition is in the Dative case.

Let’s check a few examples:

- Er liegt auf der Couch. (He is lying on the sofa.)

- Die Frau sitzt neben dem Bett. (The woman is sitting next to the bed.)

- Die Katze ist unter dem Stuhl. (The cat is under the chair.)

→ The verbs used in the above examples are

- "liegen" (to lie, to be in horizontal position),

- "sitzen" (to sit), and

- "sein" (to be) to describe where someone or something is located. We call them static verbs.

→ The prepositions are followed by a noun in the Dative case. We are told where the subjects of the sentence ("er", "die Frau", "die Katze") are, namely:

- auf der Couch (on the sofa): "die Couch" converts to "der Couch" in the Dative case,

- neben dem Bett (next to the bed): "das Bett" is "dem Bett" in the Dative case,

- unter dem Stuhl (under the chair): "der Stuhl" in the Nominative becomes "dem Stuhl" in the Dative case.

BONUS FACT

With local prepositions we also say

- where someone or something is moving or being moved to from A to B:

→ The Germans ask "wohin?", and...

→ ... you usually find a verb of movement, followed by one of the two-way prepositions.

→ The noun that follows the preposition is in the Accusative case.

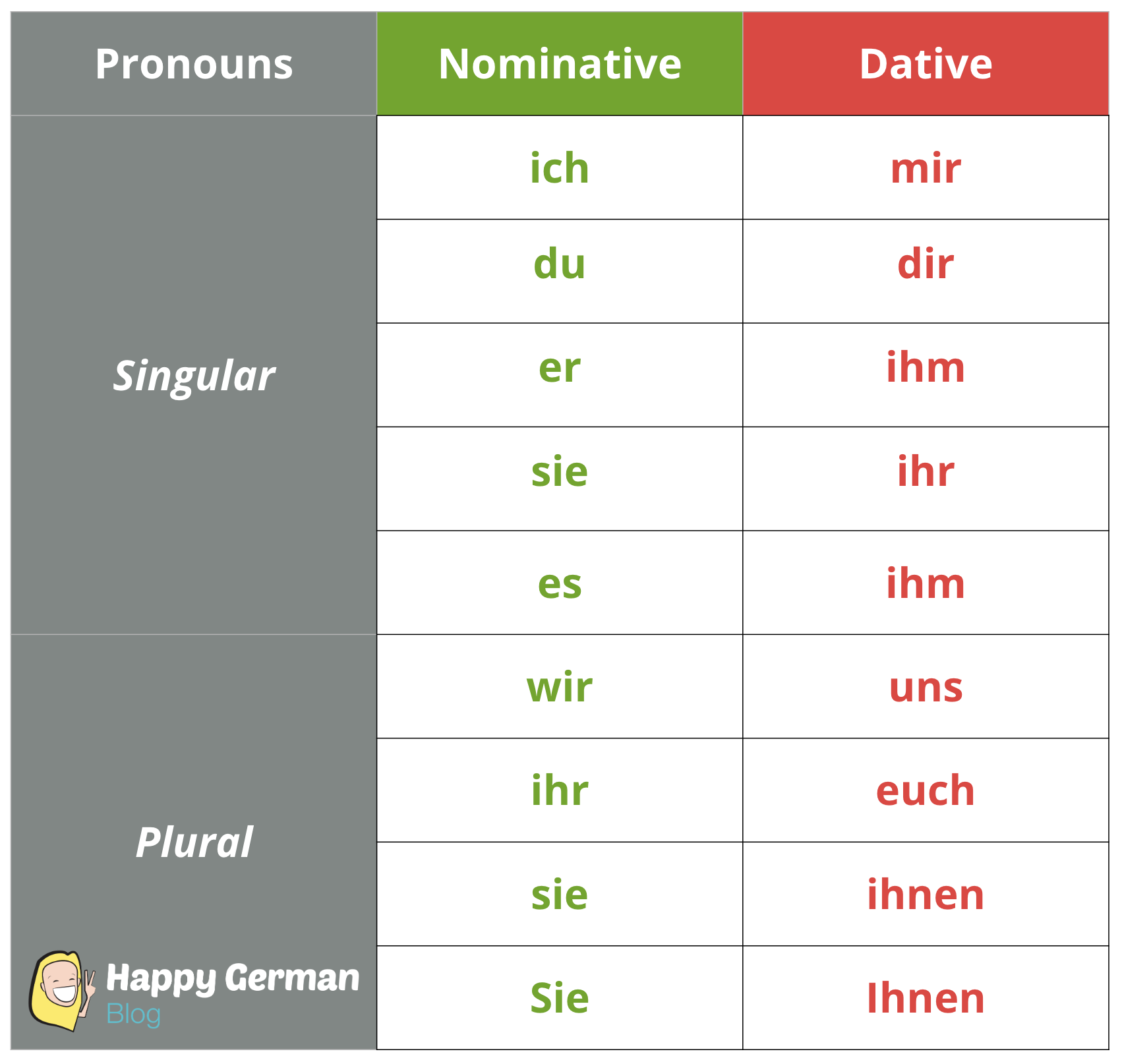

Personal Pronouns In The Dative Case

Last but not least, my dear student, let me tell you that there’s a new set of pronouns to go with the Dative. Now, there is no need to panic. I promise that soon you will be able to remember all of them because I’m sure that you’ve already heard many of the Dative pronouns without even noticing it.

Let's see:

- “Wie geht es dir?” - “Es geht mir gut, danke.” (How are you? - I'm fine, thank you.)

- “Kannst du mir helfen?” (Can you help me?)

→ Instead of "du" and "ich", you've been using their Dative equivalent "dir" and "mir" all along.

In the following table, we want to give you an overview of all the Nominative and Dative pronouns so that you can compare and practice them.

Wanna practice with Anja and rock the Dative pronouns? Here you go, have fun!

Other Uses Of The Dative Case

The Free Dative Case #freedative

Yes, we will give this particular use of the Dative its own hashtag! What do we mean by free Dative? It’s basically when someone is affected in some way by the verb. The free Dative means that the verb isn’t bound by German law to use the Dative, but the circumstances in the sentence call for the Dative, our #freedative

In the following examples, it's the person the action is being done for.

- Er öffnet mir die Dose. - (He opens the can for me.)

- Sie schneidet mir die Haare. - (She cuts my hair for me.)

There’s also something called the “benefactive” - this is when someone is doing something for themselves, they use a reflexive pronoun in the Dative case to say they’re doing the action for themselves. This is pretty colloquial and you’ll hear it a lot in spoken German.

- Ich gönne mir ein Eis. - (I treat myself to an ice cream.)

- Ich hole mir einen neuen Hund. - (I get myself a new dog.)

Und? Ich gönne mir ein paar Chips...

(So what? I'm treating myself to some chips...)

Sometimes the Dative can be replaced by “für” (+ Accusative) to tell whom something is being done for.

- Meine Mutter hat mir einen Mantel gekauft. / Meine Mutter hat einen Mantel für mich gekauft. - (My mother bought me a coat./ ...bought a coat for me.)

The “Dative Of Dis-/Advantage” - When Something Bad (Or Good) Happens To Someone

- Mir ist was Dummes passiert. (Something stupid happened to me.)

Sometimes I can be pretty clumsy and if you’re like me and feel like you have two left hands sometimes, it’s good to know this expression.

When the sh*t hits the fan, sometimes in German we’ll say it as if it happened to us.

For example:

- Mir ist das Glas runtergefallen. (The glass fell down on me - not literally the glass fell onto me but rather I was holding it and it fell down, almost like it did that to me.)

- Mir sind die Pflanzen gestorben. - (The plants died on me.)

However, we can also hear expressions like the above for nice things that happen to us, like

- Heute ist mir was Tolles passiert. (Today something fantastic happened to me.)

Congratulations! You have made it out of the Dative forest alive!

Wie geht es dir? - Haha, yes, there it is again, the Dative case. Seriously, I’m very proud of your accomplishments. You really learned a lot today. I know it’s not easy and it will take a lot of practice and effort. Remember, repetition is key, so read out loud, and more than anything, have fun learning. I’m sure we’ll see each other again very soon.