The Accusative Case In A Nutshell

We have noticed that students struggle differentiating between the Dative and the Accusative case. So, here’s an essential guide to help you feel more confident with these two cases!

In grammar lingo, the object in the Accusative case refers to a person or a thing that the verb is happening to. In an English sentence it is often the direct object. However, it’s much easier to remember the following definition:

The Accusative case is used after certain verbs and after certain prepositions.

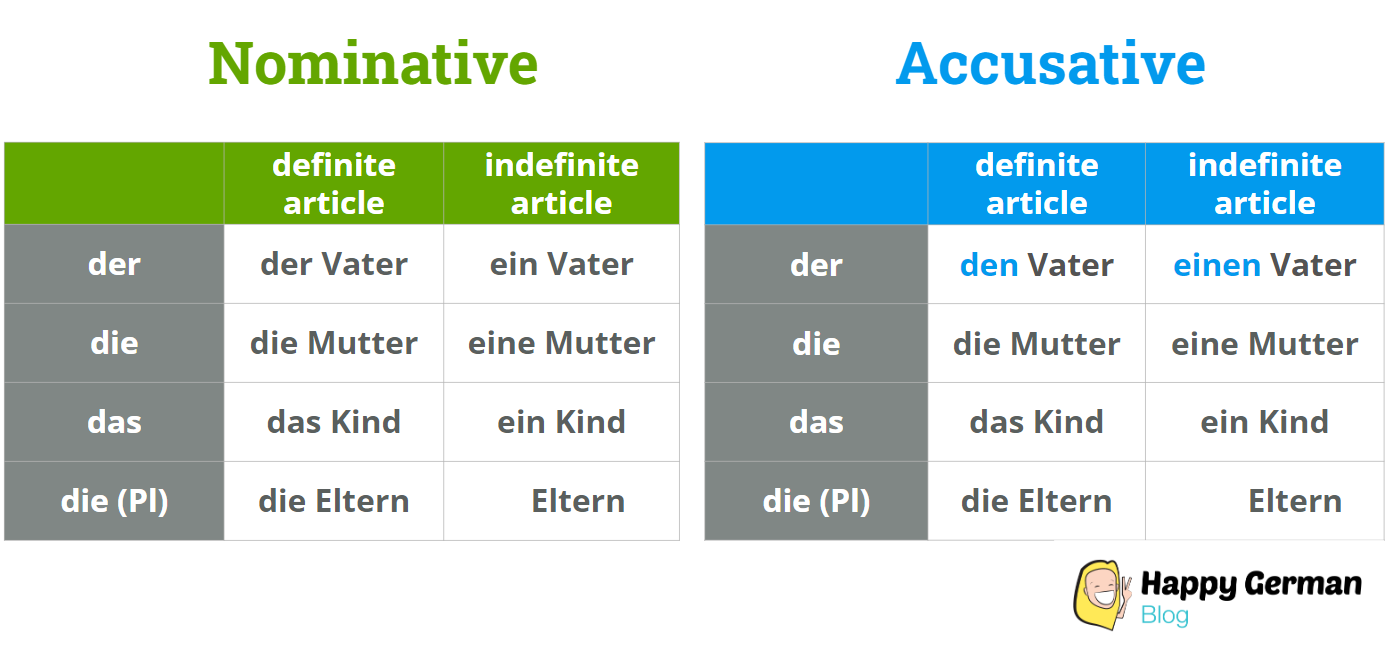

In the Accusative case, there’s a minor change only in the masculine articles. All the other articles stay the same. Check it out in the grid below.

The Accusative Case After Certain Verbs

This grammar case is pretty simple.

- First of all, we have two articles that need to be changed - the definite and indefinite one in masculine gender only.

- Secondly, for most of the German verbs that take an object, it'll be in the Accusative case.

Here are some common verbs that are always followed by an object in the Accusative case:

- sehen (to see) - Ich sehe einen Salat. (I see a lettuce.)

- kaufen (to buy) - Ich kaufe einen Salat. (I buy a lettuce.)

- haben (to have) - Ich habe einen Salat. (I have a lettuce.)

- machen (to make) - Ich mache einen Salat. (I'm making a salad.)

- essen (to eat) - Ich esse den Salat. (I'm eating the salad.)

Ich esse einen Salat.

(I'm eating a salad.)

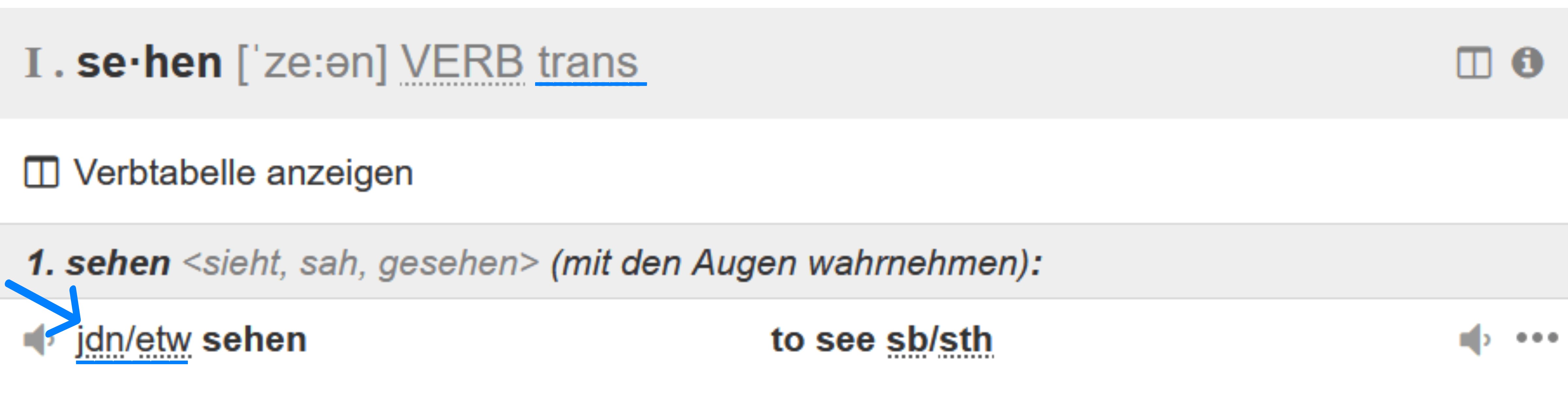

If you don't feel 100% sure whether a verb needs the Accusative or not, you can take a look at a dictionary.

Right in front of the verb in question, you'll find an abbreviation that indicates a case.

- If you see the abbreviation "jdn" for jemanden (someone), you can be sure that you will need the Accusative case.

- Additionally, the abbreviation "trans" after VERB is not a hint at the verb's gender identity. It's short for transitive, which means it is followed by an object. And the object is, you guessed it, in Accusative case.

To learn and practice more verbs that take the Accusative, watch this video with plenty more practical examples!

The Accusative Case After Certain Prepositions

When it comes to prepositions, you should know the following: There are prepositions that always stick together with their cases like BFFs, and in the given list below you can be sure that they will always use the Accusative.

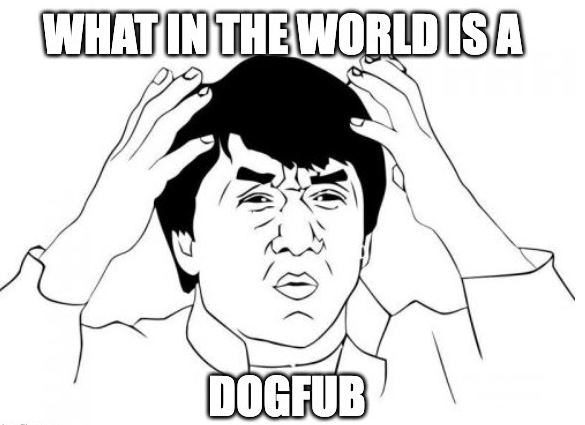

Let’s take a closer look at our best friends forever. In this case the prepositions that will only go to a party with the Accusative. We’ll call these friends DOGFUB, like the acronym for the prepositions they represent.

Was in aller Welt ist ein DOGFUB?

- durch (through) - Wir fahren durch den Tunnel. (We drive through the tunnel.)

- ohne (without) - Ich gehe ohne dich. (I’m going without you.)

- gegen (against) - Sie läuft gegen den Baum. (Literal translation - She walks against the tree.)

- für (for) - Die Kerze ist für dich. (The candle is for you.)

- um (around) - Sie läuft um den Baum. (She walks around the tree.)

- bis (until) - Bis nächsten Sonntag! (See you next Sunday! Literally, you're saying: Till next Sunday!)

Read their first letters from top to bottom: d - o - g - f - u - b. DOGFUB. They will stick with you, won’t they?

And just because you liked the previous video so much, here’s another one about the prepositions with the Accusative. There is a little practice session included, where you can test yourselves on what you’ve learned so far!

The Accusative Case After Prepositional Verbs

Things have been quite easy up to this point, so now it’s time for a challenge.

There are constructions of verbs with prepositions, they're called prepositional verbs, and they are followed by a specific case.

You might find yourselves with a verb that usually takes the Dative case. However, in combination with a certain preposition it will be followed by the Accusative. Don’t worry, here are some examples to clear things up a bit.

- glauben (to believe) - Ich glaube ihm. (I believe him.)

→ Here you can see that the verb “glauben” takes the Dative case.

But watch what happens now when we add the preposition "an".

- glauben an (to believe in) - Ich glaube an den Weihnachtsmann. (I believe in Santa Claus.)

→ As you can see, the combo of verb and preposition are now followed by the Accusative case!

Here are some more verbs with prepositions that need the Accusative.

- denken an (to think of/about) - Ich denke an dich. (I think of you.)

- sprechen über (talk about) - Ich spreche über ihn. (I talk about him.)

- sich interessieren für (to be interested in) - Wir interessieren uns für den Film. (We’re interested in the movie.)

- sich erinnern an (to remember) - Er erinnert sich an den letzten Urlaub. (He remembers the last vacation.)

Ich interessiere mich für den Film ... und für das Popcorn.

(I'm interested in the movie...and in the popcorn.)

The Dative Case In A Nutshell

It’s time to move to our next case: The Dative case. In most grammar books, you will find the following definition of the Dative case. It’s typically used after certain verbs that indicate giving and receiving, etc. Very often it is referred to as an indirect object (in English, that is) indicated by the word order or a phrase introduced by ‘to’ or ‘for’.

- helfen (to help) - Ich helfe meiner Schwester. (I'm helping my sister.)

- antworten (to answer) - Er antwortet mir. (He's answering me.)

→ In these two examples, you can see quite clearly that after "help" and "answer" we have an object in receiver position.

Let’s not make it complicated, though. We can use the following definition for the Dative:

We use the Dative case after specific verbs and prepositions.

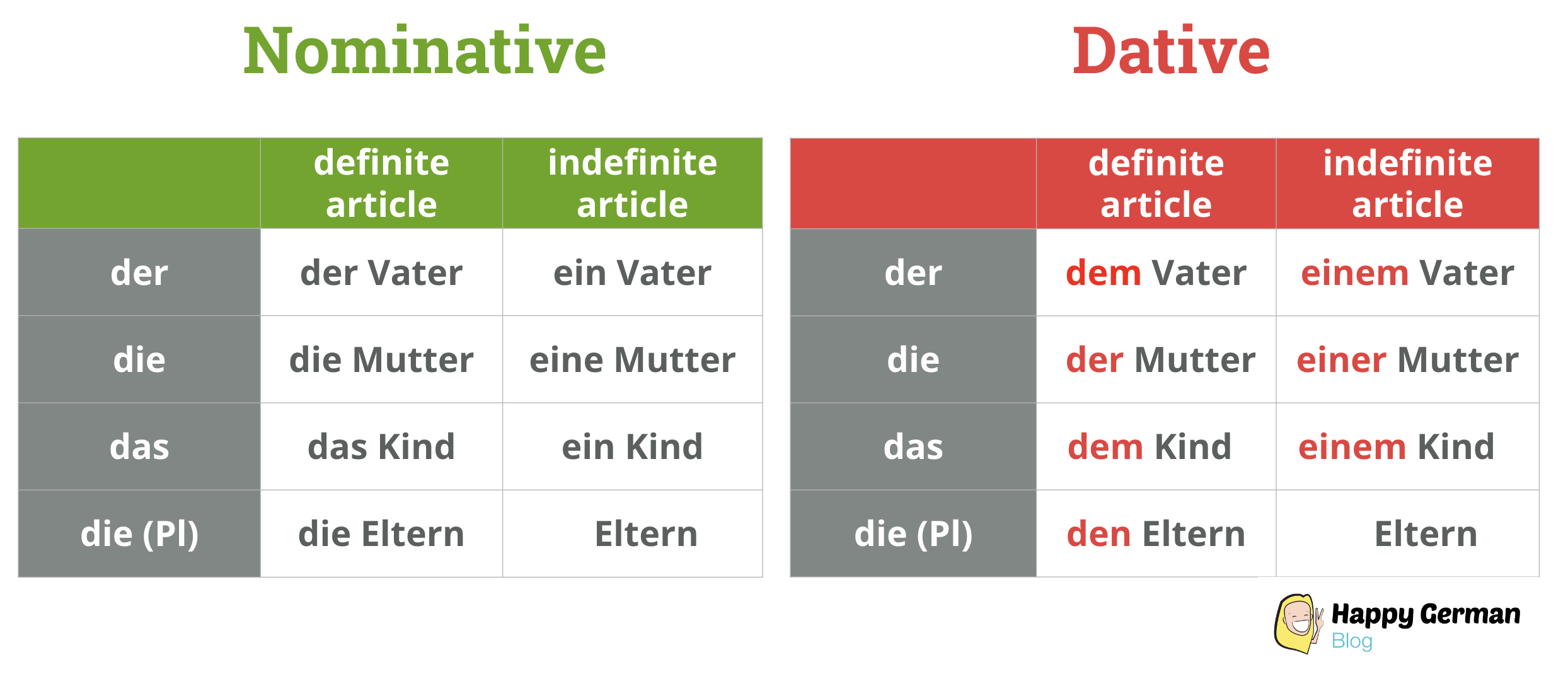

In the Dative case we have more changes to the articles than in the Accusative case. Here’s an overview.

The Dative Case After Certain Verbs

There are a number of verbs that need the Dative case only. Unlike the Accusative case, we’re talking about a pretty small number of verbs, which makes it very easy for you as a student.

Here are just a few verbs with examples:

- begegnen (to meet) - Sie begegnet einem Mann. (She meets a man.)

- gefallen (to like) - Der Mann gefällt ihr. (She likes the man. Literally: The man is to her liking.)

- schmecken (to taste) - Ihr Kuchen schmeckt ihm gut. (Her cake tastes good to him.)

Sein Obst schmeckt ihr.

(She likes his fruit. Literally: His fruit is to her liking.)

And now, enjoy this video about the 10 most important Dative verbs and take the opportunity to practice a little.

Of course, you don’t have to memorize all these verbs immediately. You’ll remember them as you go along. If you are a little unsure of which case to use, just do the following:

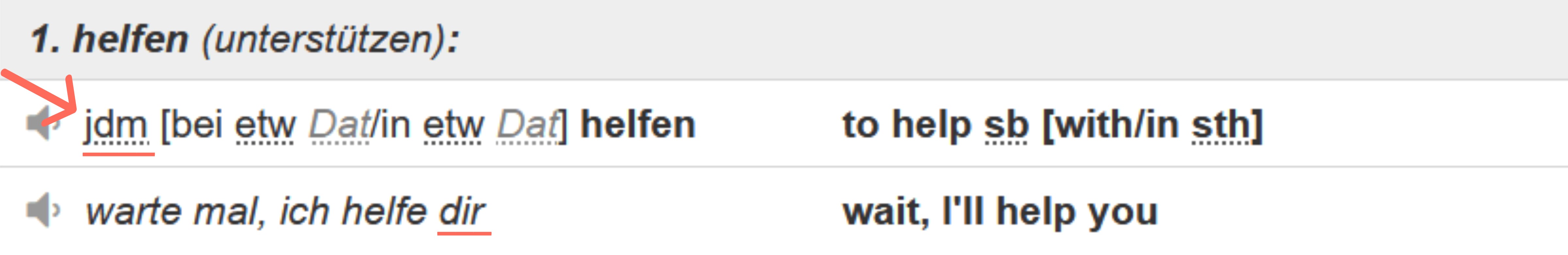

Look up the verb in question in a dictionary and you’ll find the information you need as follows:

If you see the abbreviation jdm in front of the verb in question,

it indicates the Dative case is needed, as jdm is short for jemandem (to/ for someone).

The Dative Case After Certain Prepositions

In a section at the beginning, we talked about the prepositions (DOGFUB, remember?) that take the Accusative case only. Now, we will learn about the prepositions that are followed by the Dative case only. I suggest you learn these prepositions by heart.

Here are the Dative prepositions with examples:

- ab (from): Ab dem ersten September. (From the first of September.)

- aus (from): Er kommt aus der Schweiz. (He’s from Switzerland. → Note here that Switzerland in German is “die Schweiz”. The article “die” is in its Dative form “der”.)

- außer (except, but): Alle sprechen Deutsch außer mir. (Everybody speaks German except me.)

- bei (at, near): Sie wohnt bei meinem Nachbarn. (She lives at my neighbor’s. → Note here that “Nachbar” requires a Dative ending -n. It is however not the plural form. There's a post on the nouns with the so-called "n-Deklination" coming up for you.)

- gegenüber (across, opposite): Wir wohnen gegenüber dem Park. (We live across the park.)

- mit (with): Wir fahren mit dem Auto. (We’re going by car. Literally: We’re driving with the car.)

- nach (after, temporal): Nach der Arbeit gehen wir spazieren. (After work, we'll go for a walk.)

- seit (since): Seit dem Abendessen habe ich Bauchschmerzen. (Since dinner I've had a stomach ache.)

- von (from, by): Das Geschenk ist von meiner Mutter. (The present is from my mother.)

- zu (to): Die Frau geht zum Arzt. (The woman goes to the doctor. → Note here that “zu” has joined with the Dative article “dem”: zu + dem = zum.)

Ich gehe zum Arzt. ...oh, nein. Doch nicht!

(I'm going to the doctor's. ...oh, no. I don't!)

The Dative Case After Prepositional Verbs

Just like for the Accusative, we also have the so-called “strong connections” for the Dative, where a verb is followed by a certain preposition that is followed by a specific case, respectively. Remember, if you find yourselves with a combo of verb and preposition, it is the preposition that rules the case.

Here are some examples of the combinations with the Dative case.

- abhängen von (to depend on) - Das hängt von dir ab. (That depends on you.)

- anfangen mit (to start with) - Wir fangen mit der Vorspeise an. (We'll start with the appetizer.)

- aussehen nach (to look like) - Das sieht nach einem Gewitter aus. (It looks like there will be a storm.)

- sich erholen von (to recover from) - Ich muss mich vom Wochenende erholen. (I have to recover from the weekend. → Note here that “von” has joined with the article in the Dative “dem”: von dem = vom.)

- sich erkundigen nach (to ask about/ for) - Er muss sich nach dem Weg erkundigen. (He has to ask for the way.)

You will come across many other combinations like these on your German journey. But do not worry, you will master them eventually!

Verbs With Accusative And Dative

As you know, most German verbs that take objects need them to be in the Accusative case. But very often you will find sentences that have both the Dative and the Accusative.

Accusative and Dative???

How can you distinguish the cases and how do you know when to use which case?

It’s very simple. You can almost always apply the following rule:

After verbs with two objects,

very often the person (living object) is in the Dative case,

while the thing (non-living object) is in the Accusative case.

Let’s look at these examples:

- jdm etw geben (to give sth to sb) - Ich gebe der Frau einen Pullover. (I give the woman a sweater / I give a sweater to the woman.)

- jdm etw zeigen (to show sth to sb) - Ich zeige meinem Mann den Park. (I show my husband the park / I show the park to my husband.)

- jdm etw empfehlen (to recommend sth to sb) - Ich kann dir ein schönes Hotel empfehlen. (I can recommend a nice hotel to you.)

- jdm etw schicken (to send sth to sb) - Wir schicken ihm einen Brief. (We'll send him a letter.)

So, as you can see, it’s down to the verb, really. And there are verbs in German that require both the information to whom (person - Dative case in German) and what (thing, matter - Accusative in German) is being done.

In a dictionary entry it will show as follows:

Remember what jdm stands for? Right, it’s the abbreviation for "jemandem", which is German for “to somebody”. In other words, it is the person to whom the verb of the sentence is “doing” something, and it needs to be in the Dative case, indicated by the ending -em.

Additionally we need to add etw, which is short for "etwas" (= something, i.e. the thing or matter related to the verb of the sentence). This latter object needs to be in the Accusative case.

- Ich habe dir einen Tipp gegeben. (I gave some advice to you.)

I think you're getting the hang of this.

Accusative and Dative? - Don't worry!

→ Literally it translates like this: Do make no worries to yourself. You got it: jdm etw machen. So, dir in the bubble above is the person who should do what? - keine Sorgen (no worries). - In other words: Don’t worry.

Hungry for more? Here’s a video with more exercises and a little surprise homework at the end.

Verbs With Two-Way Prepositions (Wechselpräpositionen) And Accusative Or Dative

And now let’s turn to a new idea, where we apply Accusative or Dative. As mentioned earlier, there are prepositions that like to hang out with the Dative case as well as the Accusative. They are prepositions that are more free spirited, let’s say they’re bisexual, the Germans call them “Wechselpräpositionen” (two-way prepositions). Check out the image below. It’ll give you a nice overview of the different prepositions.

Alright, it’s time to take a little break now. You are doing a great job! Now sit back, put your feet on the table and watch this funny video where we're playing hide-and-seek with the two-way prepositions! Enjoy!

Now, I could very much relate, if you asked yourselves:

“How am I supposed to know whether I should use the Accusative or the Dative with those prepositions?” Let’s look for some guidance:

Whenever there is a movement from a location A to location B, that means you have an ACtive situation that calls for the ACcusative case. Check the question "wohin?" (where to?)

- in (in, into) - Er springt in den See. (He is jumping into the lake.)

- an (at, to) - Sie geht an einen See. (She is going to a lake.)

- unter (under, below) - Der Mann läuft unter einen Baum. (The man is running under a tree. - Meaning, he was in location A, before he walked to location B, under the tree, to be in the shade or under cover.

)

→ The verbs in the examples above are: springen (to jump), gehen (to go), laufen (to run, to go), which means there is movement involved, in other words: Action. That is why, here, after the prepositions, we use the Accusative case.

Der Spion läuft unter einen Baum.

(The spy is running under a tree.)

Things change, however, when we have a more static situation. That’s when we use the Dative case with the two-way prepositions. Our little helper here is the question "wo?" (where?):

- in (in) - Der Fisch ist im See. (The fish is in the lake. → Note here that the preposition "in" has been joined with the Dative article "dem": in + dem = im)

- an (at, next to) - Sie liegt an einem See. (She’s lying at the lake.)

- unter (under) - Der Mann sitzt unter einem Baum. (The man is sitting under a tree.)

→ The verbs in the examples above are: sein (to be), liegen (to lie), sitzen (to sit), which means there is a static situation. That is why, this time round, after the prepositions, we use the Dative case.

Der Fisch ist im Teich.

(The fish is in the pond.)

And, of course, there is also a video about the two-way prepositions. So sit back and enjoy this interesting video! For further information, you may want to read the post that we're busy preparing for you on “Wechselpräpositionen” (two-way prepositions).

For now, use the following keys:

Two keys to understanding

whether to use the Accusative or the Dative

after the two-way prepositions:

- If there is movement (ACtion!) involved, use the Accusative.

- If there is a static situation (telling you where someone or something is), use the Dative.

And now, as usual, it's time to test your knowledge in our little quiz.